With Russia entering its second recession in six years, the country’s economic and financial hardships are starting to weigh on the Russian people and regional governments. In times of severe economic crisis, such as those in 1905 and 1998, the Russian populace and regional authorities traditionally react against federal authority, fragmenting the country. Those in power in Moscow understand this and are taking measures to ensure that they counter and prevent any social or regional backlash and dissent.

Analysis

The Russian economy has been in steep decline for more than a year and is slipping into another recession. A constellation of factors is causing the decline, including lower oil prices, the West’s sanctions and sour Western investment attitudes because of the Ukraine crisis. This has led to massive capital flight of $160 billion in 2014 and an estimated $80 billion in 2015, a volatile ruble that lost 40 percent of its value in late 2014, and a likely federal budget deficit of approximately $45 billion in 2015.

The Russian people are starting to feel the pain. In March, inflation skyrocketed from just under 7 percent the previous month to nearly 17 percent. According to a Levada poll, Russians see inflation as the most acute problem facing Russian society.

Food price inflation has risen even faster because of Russia’s ban on importing food from the European Union and the United States. According to the Agriculture Ministry, during the past six months the cost of cabbage in Russia has risen 66 percent, onions rose 40 percent, potatoes 36 percent, carrots 32 percent, and beef 10 percent. At the end of February, most Russian supermarkets announced a two-month price freeze on more than 20 socially important items, including meat, fish, milk, sugar, salt, potatoes, cabbage and apples. Some regional grocery chains, such as the ones in the Norilsk region that are run by Russia’s largest mining firm Norilsk Nickel, are taking losses to subsidize food prices.

Hardships Spawn Protests

Another area of dissatisfaction among the Russian people is the closure of medical facilities in some regions, such as Moscow, Novosibirsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow, nearly a quarter of inpatient medical facilities have been closed since November, sparking minor protests in the capital.

In addition, the economic pressure is affecting the country’s job market. Russia’s Labor Ministry estimated that some 154,800 jobs were cut in 2014, and approximately 127,000 jobs were cut in the first two months of 2015. According to Deputy Labor Minister Sergei Velmyaikin, the majority of these layoffs were at large Russian firms, such as Rosneft, Rostelecom, Avtovaz and Mechel, which are run by the state or oligarchs. There are also reports that in the Murmansk and Zabaikalsk regions, salaries for teachers have not been paid in three months. The teachers in Murmansk are petitioning their governor to ask Russian President Vladimir Putin for increased financial subsidies. The teachers in Zabaikalsk have held three minor street protests.

The federal government has allocated $300 million for employment subsidies for some Russian regional governments, such as Tatarstan, Altai Krai, Samara and Tver. These subsides are aimed at maintaining employment at regional companies such as KAMAZ, Avtovaz, AltaiVagon and Tver Carriage Works.

Sporadic minor protests have also taken place across Russia during the past month. Communist Party members in Stavropol got in coffins to protest their regional government’s low pension payouts. In Novosibirsk, farmers dumped manure in front of state-run Sberbank with signs saying, “Bankers are enemies of the people,” and, “Down with credit slavery.”

The Kremlin Offers Assistance

The worsening economic situation in many of the regions has prompted the Kremlin to call “socio-economic” meetings between Putin and many of the regional heads. During the past two months, Putin has met with the heads of the Kursk, Karelia, Astrakhan, Moscow, Tula, Irkutsk and Kaliningrad regions, and the republics of North Ossetia and Khakassia.

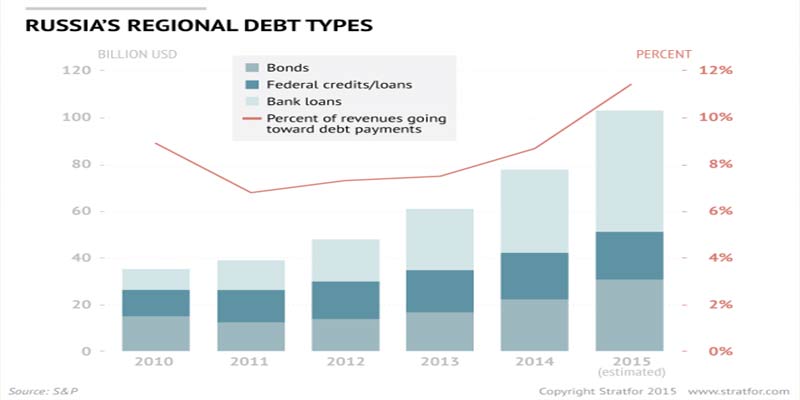

Most of the Russian regional governments are ill equipped to handle this economic crisis; 63 of the 83 regional governments are at risk of defaulting on their debt or going bankrupt in the next few years. Since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the regional governments’ debt has risen by more than 100 percent. Standard and Poor’s estimates regional government debt in 2015 will reach $103 billion. Russia’s overall government debt — the federal and regional governments combined — is around $300 billion, or 14 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product. This is small for a country as large as Russia, but the problem is that so much of the debt is concentrated in the regions, which do not have as many debt reduction tools as the federal government does.

The Kremlin is concerned that the worsening economic situation could force some of the regional leaders to break with some of the federal government’s strategies, such as how to handle protests, or how to allocate funds or pay taxes. Increasingly dissatisfied populations and business leaders as well as the federal government are pressuring regional heads. Specifically, the Kremlin wants the regional governments to continue paying extraordinarily high taxes instead of keeping the funds at home. Of the taxes and revenues generated in each region, only 37 percent stay in the regions while the rest goes to the federal government. Some funds — but not more than 20 percent — are returned in the form of subsidies.

In response, the federal government approved a plan March 20 to restructure loans the regions have taken out from the federal budget. The Kremlin is earmarking $1.6 billion for the restructuring. In addition, the payment deadlines are being moved back from 2025 to 2034.

When approving the plan, Russian Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev said, “We cannot leave members of the Federation to deal with this alone” — a nod to the Kremlin’s concerns about dissent and instability in the regions. It is difficult enough for the Kremlin to control all of Russia’s 83 regions even when there is not an economic crisis and social unrest. The Kremlin knows fragmentation and unrest can lead to government change; Putin himself came to power under similar circumstances. In order to keep their regions stable during the 1998 financial crisis, regional leaders began breaking with federal policies on how to handle protesters and on paying federal taxes.

An Eye on Dissent

Besides financial assistance programs, the Kremlin is also setting up ways to crack down on the regional leaders should there be dissent or should they not be able to control their respective regions.

On March 30, a Kremlin-linked think tank, the Civil Society Development Foundation, released a rating of the best and worst regional heads. The study was mostly rated on improvements in the regions’ socioeconomic conditions. The foundation also said it would be releasing this ranking every quarter, as if the Kremlin will now have a quarterly check on the regional leaders’ competency.

Putin has never been shy about reshuffling regional heads. Since the start of the year, he has appointed new or acting leaders in six regions: Tatarstan, Amur, Sakhalin, Yamal-Nenets, Khanty-Mansiysk and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Now it looks like Putin is ensuring that all the governors and regional heads can see where they stand and has created a system to drum up public sentiment against those governors that do not comply with Putin’s policies.

Putin tightening his grip on power may not be controversial among the Russian people. In the 1998 financial crisis, some 71 percent of Russians believed that keeping order in the country was more important than democracy, according to a Levada poll. Interestingly, Levada released a poll on March 31 that indicated 45 percent of Russians think the crackdowns that Soviet leader Josef Stalin conducted during economic hardships were justified — a sharp rise from just 25 percent in 2013. Consequently, Russians could be increasingly in favor of crackdowns and a tighter Kremlin hold, as long as the country remains stable.

Amid an Economic Crisis, Russia Contains Dissent is republished with permission of Stratfor.